A través del ojo de Atravazd Peleshian

Hablando de Peleshian se tiene que hablar de Godard, las similitudes son evidentemente notorias. Empezando con el manejo de las imagenes en películas como “Iván el Terrible” y “Angeles del pecado”, Peleshian al igual que Godard usa y recicla u numero de ciertas fotos familiares y sonidos en diferentes películas durante su carrera fílmica, como una especie de sello distintivo. Peleshian cree fielmente que la fotografía es verdadera, parando en cada imagen recobrando un cierto sentido en determinado tiempo. Reutilizar la imagen en diferentes momentos cambia la esencia y significado de esta, al igual que el uso de oraciones o frases que tal vez ya hayan sido utilizadas anteriormente pero al ser recontextualizadas vuelven a cambiar.

Pero hablando específicamente de las palabras, ahora recordamos que en ningunas de las películas de ambos directores se utilizan palabras, de hecho en el caso de Peleshian no hay ni siquiera una palabra en dialogo porque este no existe, haciendo asi un subrayado en el verdadero poder de la imagen en pantalla sin necesidad de la palabra que busca aportar sentido.

Peleshian parece ver a las personas como identidades monolíticas , cuyas ambiciones, idiosincrasias, luchas y emociones a pesar de ser particularizadas por la historia , trascienden geográficamente. La temática de Peleshian, una mirada profunda a la historia de su país que revela una gran cantidad de tragedias que lo acompañaron durante su vida. Una constante presencia de imperialismo, opresión, y varias situaciones que han atacado a Armenia desde años atrás. Tomando en cuenta lo anterior es normal y casi natural comprender las películas de Peleshian como situaciones de movimiento, de tiempo, de gente y de vida, al igual que las imágenes que por sí solas denotan este sentimiento, cambio y constante transformación. Armenia por si sola ha sido caracterizada por los movimientos y la inestabilidad que su historia nos cuenta. El constante paso del poder de un gobernante a otro y la desesperada búsqueda por encontrar un lugar donde poder asentarse y poder vivir.

“The Armenians are simply an opportunity that allows me to talk about the whole world, about human characteristics, human nature. One may with also to see Armenia and the Armenian in that film. But I have never allowed myself to do it then, and would not now.”

En toda su trayectoria fílmica, la percepción de sus películas frente al espectador, siempre permite llevar consigo un todo , mas no una sola parte en particular. A pesar de que muchos elementos se presenten repetidos durante la película su orden y su posición alteran la visión del espectador de distintas formas, manteniendo una buena distancia con el espectador, se le otorga un ojo omnisciente que le da la sensibilidad de ver mas alla, de poder comprender los problemas y las situaciones que se presentan, no solo cosas en particular sino un todo. Tal vez esta sea la razón por la que no existen personajes en las películas de Peleshian , es muy difícil poder distinguir entre el material previamente seleccionado al material que se construyo para la película, para él los personajes ya vienen implícitos en todo tipo de historia, esperando a ser descubiertos por el espectador.

Peleshian desarrolló un estilo cinematográfico muy particular, conocido como montaje a distancia, en donde se combinan la percepción de profundidad así como imágenes de manadas de antílopes o animales en plena acción. El uso de material de archivo, también es un elemento característico en sus películas aparte de su propias tomas.

Me atrevería a decir que sus películas se encuentran entre la línea del documental y la ficción, historias con diferentes caras que a pesar de no ser de larga duración, nos atrapan desde un principio.

Sometimes I don't call my method "montage". I'm involved in a process of creating unity. In a sense I've eliminated montage: by creating the film through montage, I have destroyed montage. In the totality, in the wholeness of one of my films, there is no montage, no collision, so as a result montage has been destroyed. In Eisenstein every element means something. For me the individual fragments don't mean anything anymore. Only the whole film has the meaning."

Peleshian.

“The seasons of the year, The end”.

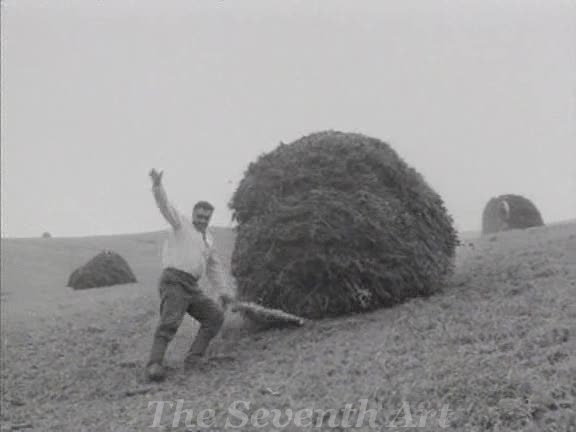

In the first section Peleshian presents us images from sunny day in an idyllic pastoral life, where a family of herdsmen lead their sheep through a dark tunnel and then to light. We then see a group of young men dragging huge stacks of hay down a hill slope and then trying to stop it. This scene, once more, illustrates our can’t-live-with-can’t-without relationship with nature, but never once becoming a contrived symbol or a metaphor. It is merely a glimpse of life which reveals a fact rather than expressing it. The same would be true of the sequence that is to follow, where the herdsmen risk their own lives in order to salvage their herd that is caught in the rapids. The film then shifts to an ethno-documentary mode as we witness a marriage ceremony in which a cow forms as much an integral part as the bride and the groom. In a rather prolonged scene that follows, in what looks like an amusing sport, we are shown a few men, each holding a sheep in his hand, sliding down a snowy hill, refusing to let go of the animal – A practice that is as strange as man’s kinship with nature – living with it, living against it, living despite it, living for it and living because of it.

Although Life would have made an astounding end to a solid filmography, it is End (Verj, 1994) that provides a more rounded closure to it. End is a series of shots inside a speeding train, the passengers of which are of diverse age groups, ethnicities and emotional statuses. The train itself feels like a microcosm of the whole world, each of whose inhabitants is moving towards an individual destination but the totality of them going in the same direction. End is perhaps the kind of vision that Damiel (Bruno Ganz) saw in the train in Berlin in Wings of Desire (1987), considering the voyeuristic nature of the camerawork in this film. There are also a few outdoor shots, of mountains (again) and of the sun, that punctuate End. If Life’s ending shot seemed to seal Peleshian’s faith in humanity, the closing shot of End brings back the lifelong dialectic between cynicism and optimism that has so consistently characterized Peleshian’s work. We see the train, after a very long passage through the darkness of the tunnels, suddenly plunging into blinding light. Before it is revealed to us what lies beyond, the end credits roll. Is it a man-made apocalypse foreseen by Earth of People? Is it the Great Armenian Earthquake? Or is it the ultimate redemption for humanity that Life suggests? Looking back at Peleshian’s body of work, it is probably the latter.

www.parajanov.com/seasons

www.imdb.com/name

www.listal.com/director/artavazd-peleshia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artavazd_Peleshyan

www.cinemaseekers.com/

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario